There is an editorial in Nature this week which has attracted a lot of criticism on the internet. "Open access is tiring out peer reviewers" by Dr. Martijn Arns suggests that a rise in scientific publications is due to increased numbers of manuscript submissions to open-access journals, and that this is placing increased pressure on peer-reviewers.

Whether or not Dr. Arns is correct about open access, it is fair to say that the number of publications is increasing. Welcome to the world of 'publish-or-perish', where even undergraduates are pressured to have maybe one paper under their belt in order to be competitive for grad school places. An increase in submissions is inevitable under these conditions. But this is not what I am writing about here.

Dr Arns complains that reviewers are "overworked and fatigued" and suggests that "quality will suffer — across the board — unless something is done". Under the free market system, this translates to increased demand for the commodity that is academic reviewers. This should consequently be reflected by an increase in price for that commodity, leading us to the question:

Would reviewers be less "tired" if journals started properly compensating them?

The subject of paid reviewers is controversial, and I will not go over the pros and cons here. Personally, I believe that academia is best served by a spirit of collegiality where review is freely provided to fellow researchers. At the same time, in a world where academics are being financially squeezed from all sides, it is immoral (not to mention poor business practice) to simply give away one of our most marketable skills to massive-profit-making multinational publishing houses.

Some researchers have said that they will simply refuse to perform free reviews for profit-making journals, but this is not an option for early-career scientists, who need to publish and review for these "prestigious" journals as they are held in higher esteem by employers and tenure boards.

Still, in this world of corporate universities, I wonder how long it will be before college CEOs stop allowing their paid professors to simply give their time away in free consultancy for multinational publishing corporations. If this was to happen, I am not sure how much of a backlash there would be from already overworked professors.

But how could reviewers be compensated for their work? Direct financial compensation comes with its own problems, and is never going to happen anyway; however, I think that "journal credit" for reviews is a good compromise. I have received this kind of compensation for two of the reviews that I have conducted, in the form of 12 months free online access to an otherwise subscription-based journal.

I suggest that a widening of this system to the university level would be a fair form of reviewer compensation: for each review, the reviewer's institutional library would receive one credit point from the publishing house, which could then be used to offset journal subscription costs. This would incentivize peer review for the reviewer and parent institution, and would cost little for the publishers. Universities with large research programs would probably attract more peer review "business" and could then either keep library costs down, or subscribe to more journals. An increase in journal subscriptions would benefit publishers, and authors whose work is published in journals with increased readership. Reviewers would at least feel like they got something back for their labor, and maybe would be held in greater esteem by their institutions.

I have not seen this idea suggested elsewhere, so I decided to throw it out here. My 2 cents.

Saturday, November 29, 2014

Monday, November 3, 2014

Another Morrison mystery: vintage photos of dinosaur digs from ~1912

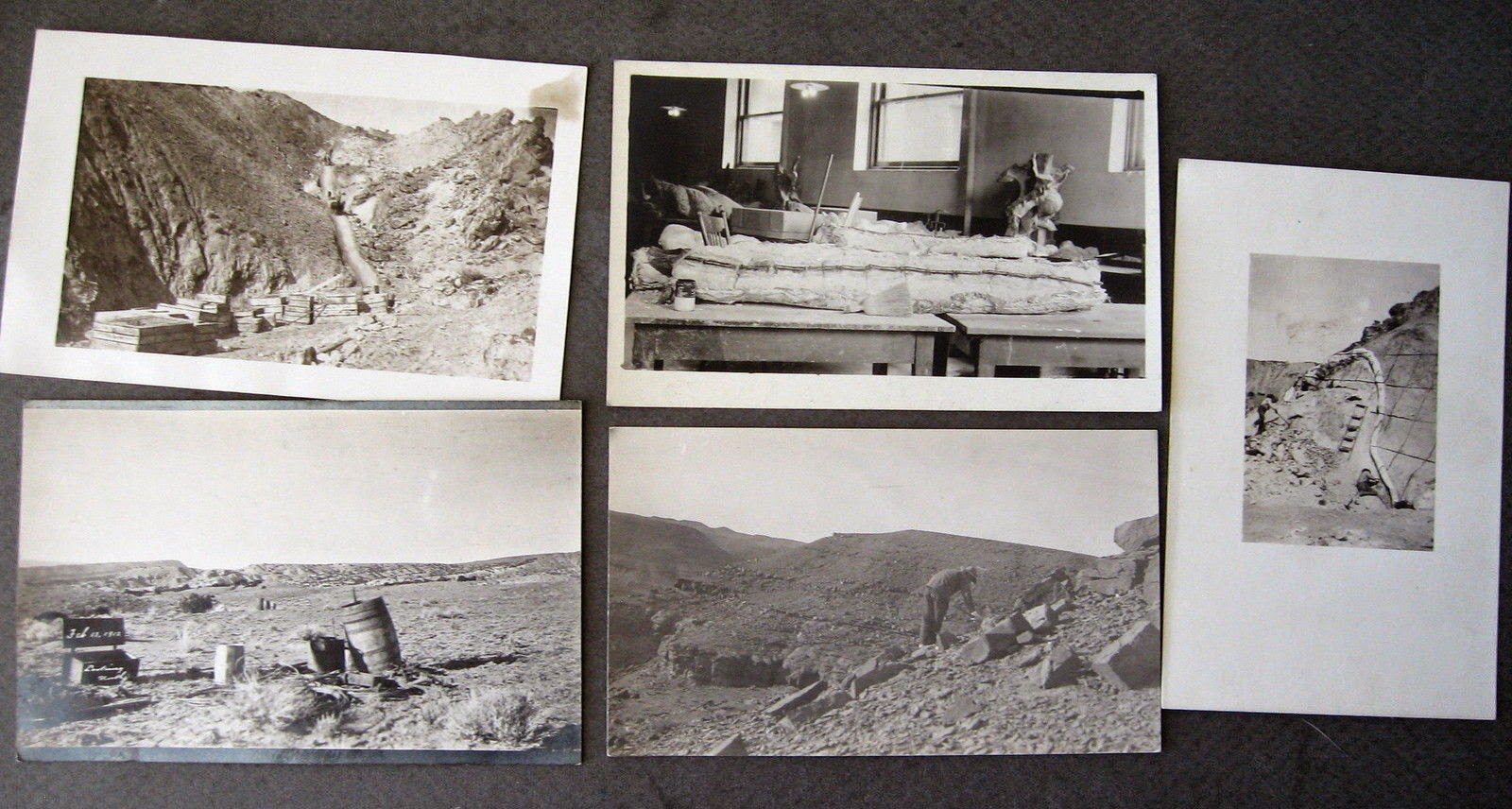

Okay, so I haven't got around to making a post on fieldwork yet, but I thought I would put together a quick post about some additional vintage Morrison Formation fieldwork images from ~1912. Pictures with a story to tell...

These five Real Photo Postcards (RPPCs) recently sold on Ebay (I didn't bid on them). I had not seen any of these images before, so maybe they are each truly one-of-a-kind RPPCs; if this is the case then they may be unique records of collecting during this era.

Fortunately, the seller included high-resolution photos of the cards, which depict some intriguing details. Here is the full set, and a view of the reverse sides (see later for closeups):

I am not so sure that all of the cards in this new set were similarly mass-produced. The bottom left and bottom centre RPPCs are full-frame prints, and the bottom left RPPC has some handwritten text added to a dark area of the image. I suspect that these two might be part of a larger print run. However, the three photos with white borders are poorly framed, differing sizes, and one is slightly out of focus. Not very professional. These are also the more interesting cards.

Let's take a closer look.

It's possible that the field crew were in the Uinta deposits searching for a range of different fossils, so maybe they really were looking for mammals. I am not familiar with the Eocene exposures in this area, so I cannot say whether or not the outcrop patterns of the cliffs look Eocene, or whether they look more like the much older Jurassic Morrison Formation (~150 Mya). However, the following photos definitely look Morrison to me.

The fourth photo (unfortunately blurred) appears to show a near vertical cliff face with a long thin

plaster jacket adhered to it. You can just about make out the shape of some large bones at the far end of the jacket. The uplifted rocks and size of the bones

suggest to me that this is an excavation into the Late Jurassic Morrison

Fm (maybe even Dinosaur National Monument itself), and that the long

thin jacket is a sauropod dinosaur tail.

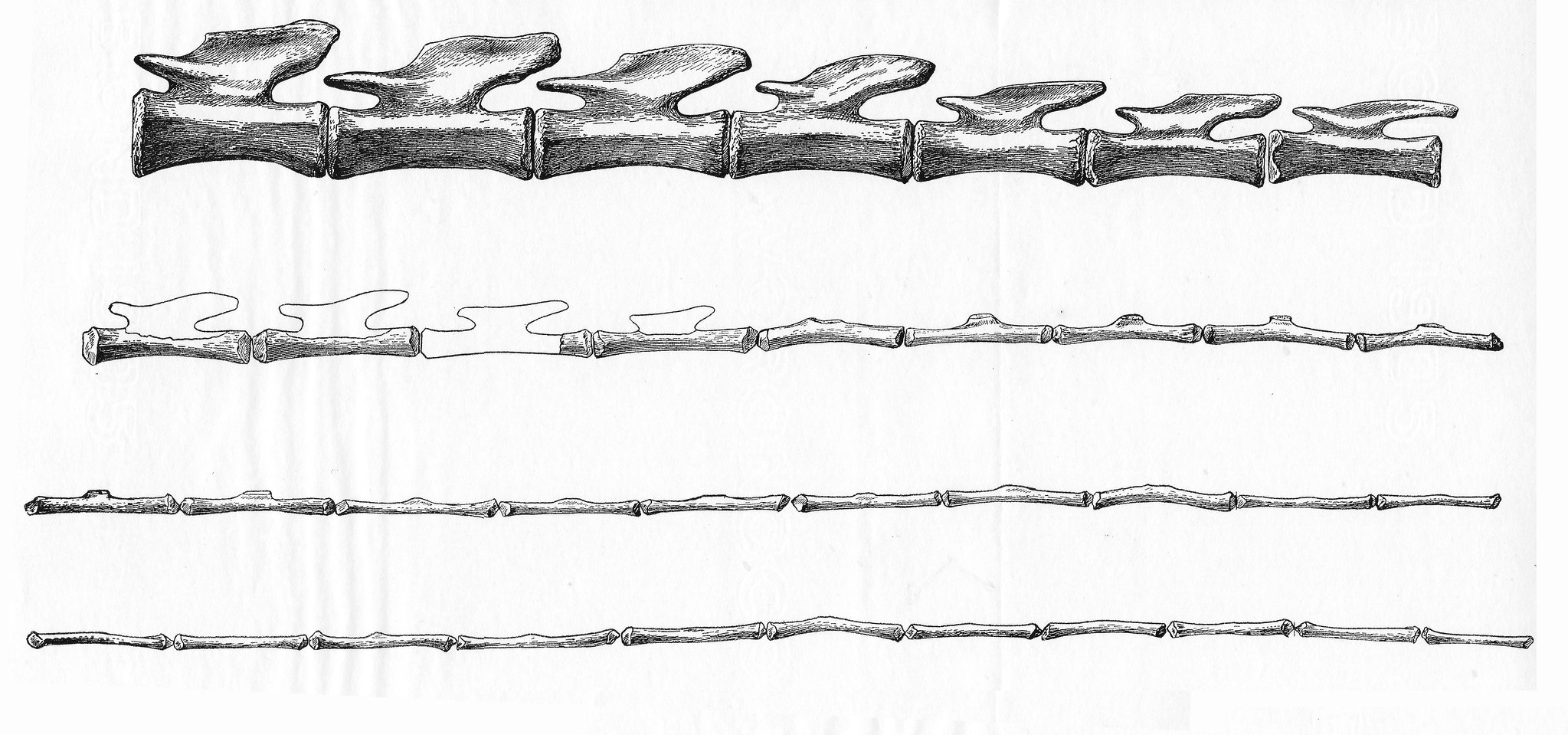

The fifth photo possibly shows the long narrow jacket from PC4 being prepared in the lab. In the foreground is an opened jacket containing what appears to be an articulated series of elongated vertebrae from the end of a

diplodocid sauropod tail (see below). In the background is another part of the jacket, next to what looks like a

sauropod neck vertebra, with more vertebrae in the sandbox (back left).

Are these postcards unique images of an important fossil expedition? The nature of RPPCs makes this a possibility, but I do not know. However, there cannot be many historically collected diplodocid tails, so perhaps someone with better knowledge of the subject can shed some light on this little mystery. Either way, I enjoy seeing these old-timer field photos. I hope you do too!

These five Real Photo Postcards (RPPCs) recently sold on Ebay (I didn't bid on them). I had not seen any of these images before, so maybe they are each truly one-of-a-kind RPPCs; if this is the case then they may be unique records of collecting during this era.

Fortunately, the seller included high-resolution photos of the cards, which depict some intriguing details. Here is the full set, and a view of the reverse sides (see later for closeups):

|

| The set of recently sold RPPCs: mass produced or unique amateur photographs? (image from Ebay) |

|

| Reverse side. The writing reads "Hunting for bones of ancient Mammals in the Uinta Deposits" (sic). (image from Ebay) |

Unique images?

You might remember from my previous blog post that earlier this year I purchased some RPPCs showing early 20th century dinosaur excavations in the Morrison Formation. I was excited as many RPPCs are unique, created by amateur photographers using a special Kodak camera with which you could print your own photos as postcards. However, I concluded that my postcards were not unique as they had text added to the front, making them look semi-professional at least, and I had found another example of one RPPC for sale elsewhere. My cards were from c.1903-30, and quite rare, but they were part of a larger print run. Darn.I am not so sure that all of the cards in this new set were similarly mass-produced. The bottom left and bottom centre RPPCs are full-frame prints, and the bottom left RPPC has some handwritten text added to a dark area of the image. I suspect that these two might be part of a larger print run. However, the three photos with white borders are poorly framed, differing sizes, and one is slightly out of focus. Not very professional. These are also the more interesting cards.

Let's take a closer look.

|

| PC1. A view of outcrop, presumably where the photographer was searching for fossils. Full-frame RPPC, (image cropped from Ebay photo) |

PC1

The first image shows some badlands in the distance, and some barrels (maybe field equipment, or watering for cows). It's pretty unexciting stuff, but it contains the handwritten caption "Feb 13, 1912 Looking North", providing us with an age consistent with the time when RPPCs were available (1903-30), and when there were significant excavations in the Morrison Formation, and surrounding areas. |

| PC2. Pack mules moving boxes of fossils? White-border RPPC, (image cropped from Ebay photo) |

PC2

This second photo depicts a series of boxes at the end of a trail. In the distance, some animals (pack mules?) can be seen moving toward the boxes. There are not many other clues in this image to inform us of what is going on, unless someone recognizes the trail. Are there fossils in those boxes? |

| PC3. A man searching among blocks of sandstone exposed in some badlands. Full-frame RPPC, (image cropped from Ebay photo) |

PC3

This RPPC shows a man investigating what appears to be blocks of sandstone exposed in badlands topography. If the Ebay seller arranged the postcard reverse sides the same as the front (see above photos), then this is the card that has "Hunting for bones of ancient Mammals in the Uinta Deposits" (sic) written on the reverse. Were the fossil hunters looking for ancient mammals? There are certainly many large extinct mammals known from the Uinta basin and Uinta mountains of Utah, including the bizarre-looking Uintatherium: an enormous herbivorous mammal that lived during the Eocene (~45-50 Mya), and whose remains are well-known from the Bridger and Wakashie Formations of Wyoming and Utah. |

| The dinoceratan mammal, Uintatherium. Is the man photographed in PC3 looking for remains of giant Eocene mammals? (image from Wikipedia, originally from Scott, 1913) |

It's possible that the field crew were in the Uinta deposits searching for a range of different fossils, so maybe they really were looking for mammals. I am not familiar with the Eocene exposures in this area, so I cannot say whether or not the outcrop patterns of the cliffs look Eocene, or whether they look more like the much older Jurassic Morrison Formation (~150 Mya). However, the following photos definitely look Morrison to me.

| |

| PC4. Two men digging into a steeply inclined cliff with what is probably a long plaster jacket. White-border RPPC, (original blurred image cropped from Ebay seller image) |

|

| PC5. Is this a photo of the jackets from PC4? |

| ||

| Vertebrae from the end of a Diplodocus tail,as figured in Holland, 1906; The vertebrae in the jacket in PC5 look almost identical to the lower two rows. |

|

| The tail of Diplodocus had a long thin whiplash-like end. (image source: Columbia.edu) |

Are these postcards unique images of an important fossil expedition? The nature of RPPCs makes this a possibility, but I do not know. However, there cannot be many historically collected diplodocid tails, so perhaps someone with better knowledge of the subject can shed some light on this little mystery. Either way, I enjoy seeing these old-timer field photos. I hope you do too!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)